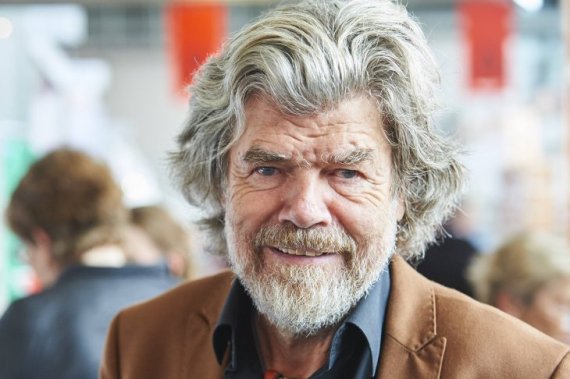

When Reinhold Messner (73) and Peter Habeler (75) reached the 8,848-meter high summit of Mount Everest on May 8, 1978 without the use of artificial oxygen, the climbers crossed what was considered an impossible border and marked a milestone in the history of mountaineering.

Just in time for the 40th anniversary of this border crossing, Reinhold Messner is showing his third directorial work with “Mount Everest – The Last Step.”

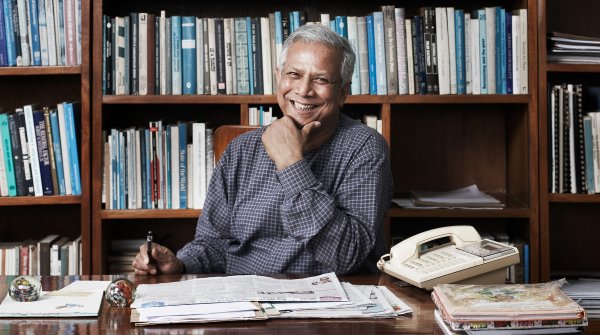

ISPO.com spoke with Messner, who was awarded the ISPO trophy in 1989, about the legendary ascent, mountain sports today, and his work as a director.

ISPO.com: On May 8, 1978, you and Peter Habeler reach the summit of Mount Everest around 1:15 pm. How present is this arrival to you 40 years later?

Reinhold Messner: The feelings are very present. But I couldn’t have named the exact time off the top of my head without reading my notes first. That number is irrelevant anyway. We only carry a remembered realness within us, not reality.

But what I do remember very well: When I reached the summit, I crouched down and immediately tried to unpack my camera, which was awkward because I had to take off my overgloves first. Not a safe thing to do, because it was terribly cold and windy. Above all, one summit scene has branded itself in my memory: Peter leans over to me in a thundering wind, and we hug and thank each other. A very emotional moment! The outside world was infinitely far away.

We never lost a single thought on the idea that we had succeeded in creating a sensation, something perhaps unique. We were on top, but now we had to get safely back down. That was the only concrete thought I could still grasp up there.

At the time, climbing Everest without additional oxygen was considered impossible. Were you reckless back then, or confident?

Without a certain easiness – I’m consciously avoiding the word carelessness – such an undertaking wouldn’t be feasible. It takes the knack to dare something like that. Despite good preparation, sophisticated logistics, and the best training, such an enterprise always poses an incalculable residual risk that you have to accept.

I was occupied by the idea of trying Everest without oxygen longer than I’ve ever been with anything else. Already in 1972 Wolfgang Nairz, Oswald Oelz, and I decided to try Everest after the Manaslu expedition. It took us six whole years to get a permit to climb Mount Everest.

In 1978, you joined an Austrian expedition.

Peter and I were involved as a stand-alone team in the Everest expedition of the Austrian Alpine Association, whose goal was to send the first Austrians to the summit of Everest. Peter and I were completely independent within this group as a team of two. We paid into the expedition fund so we’d be allowed to share the base camp and the food.

We alternated ascending with all of the team members in the joint preparatory work, until Peter and I had built the last camp for us on the South Col. From there, we were on our own on the way to the summit and back again.

How did you overcome the dreaded Khumbu Icefall back then?

Naturally, icefall doctors didn’t exist yet. In the team we determined the ascent route, the route to the South Col, so we also secured against the Khumbu icefall together. Without Sherpas going first, of course. The task of our carriers was guaranteeing supplies. Today it’s the opposite. Sherpas, who are now great mountaineers, prepare the entire route up to the summit in advance and later accompany their clients on the ascent. In the dangerous Khumbu Icefall, which changes daily, Sherpas climb in regularly and check ropes, ladders, bridges and, if necessary, change the route at short notice.

At that time, brain researchers had warned emphatically against climbing Everest without bottled oxygen. How did you prepare yourself mentally and physically for this risk?

I had already climbed three eight-thousanders before Everest, and knew how my body reacted at that altitude. Peter Habeler (here in an interview with ISPO.com) already had eight-thousander experience, as well. So neither of us were anywhere near starting from scratch. This self-power, which grows with experience, was a basic requirement for this undertaking. Besides, Peter and I didn’t set out with the intent of reaching the summit at any cost. We wanted to go as far as our bodies or our fear allowed. We were ready to give it a try and had planned for a possible turnaround.

How were your tactics laid out?

I didn’t really take the warnings from doctors and scientists seriously for historical reasons, because I knew that Edward Felix Norton had already climbed above 8,500 meters without oxygen in 1924. With pickaxes, gaiters, hobnailed shoes, in a jacket instead of a down suit. The problem at that time was that climbers had only managed 25 to 30 meters per hour at this altitude, completely exhausted.

It was clear to me that we needed a different tactic, reversed logistics, in order to still be halfway strong at the crucial summit attempt. So Peter and I spent the night before the summit comparatively low down, at about 8,000 meters. Start lower, less oxygen deficit, climb fast on the summit day – that was our plan, which wasn’t without controversy. Back then, Peter Habeler was one of the best and fastest mountain climbers in the world, and thus the ideal partner. So, to spend as little time as possible in the life-threatening death zone, our tactic was: up fast, down fast.

Let’s say that Everest was 200 meters higher, that is, a nine-thousander peak. Would an ascent without additional oxygen still be possible?

At some point it’s just over, because your blood starts boiling at that height. 200 meters above the summit of Everest – and this has been scientifically proven – the ultimate limit of hypoxia tolerance has long since been exceeded. Without enough oxygen in your body, not only does your performance plummet. Your brain also suffers from the lack of oxygen. Undersupplied for a longer period of time, your willpower, mental capacity, and decision-making power start to dwindle. Without will, the all-decisive engine at altitude, you can’t take another step. It’s a bit of an exaggeration, but you mutate into a zombie in air that thin.

Did you deposit bottled oxygen somewhere in case of emergency?

We hadn’t deposited any oxygen.

Suppose that, at that time, you would have had the opportunity to take a piece of equipment from today. What would you pick?

It would most likely be a satellite phone to check the weather forecast. Today, Everest is no longer a particular challenge. In contrast to our minimalist mountaineering, an infrastructure for mountain tourists, a runway from the base camp to the summit, is created in advance. You climb the mountain with bottled oxygen, which reduces the mountain to an average six-thousander. Today, only a few traditional mountaineers worldwide still follow my path.

What do most of them do?

The vast majority climbs in the hall on plastic handles, or in well-secured, drilled-in sports climbing routes. On the famous mountains like Kilimanjaro, Mount McKinley, Manaslu, Aconcagua, etc., slopes are prepared for people who are unable to climb on their own.

At a young age, you drove an orange Porsche and wore a Rolex. Was it easier in the past to finance your life as a mountaineer?

The Everest Rolex wasn’t associated with money. I made it available for the “Light into Darkness” campaign. It was sold at auction. And the Porsche was acquired in a totally normal fashion. Sponsorship has only increased as a result of the enormous growth of the outdoor industry. To some extent, I even helped to lay the ground for this, and I am pleased that many more professional mountaineers are making a living today than in the past.

After “Still Alive” and “Ama Dablam - Drama on the Holy Mountain,” “Mount Everest – The Last Step” is your third directorial work. Were you able to use original footage? Where were new film scenes shot?

The original material from Leo Dickinson is the foundation. This film was shortened in part and filled in with current close-ups of Everest to bring the individual scenes into a clear overview. Today, we can screw special cameras to helicopters and take wonderful pictures that give you an overall impression.

We added newly shot, scenic sequences that couldn’t be filmed in 1978 for logistical reasons, and incorporated shots taken on location in Nepal and in Sulden in the Madritsch region. My son Simon and his climbing companion Philipp Brugger reenacted these scenes in the original equipment of that time.

How happy are you as a father that Simon didn’t become a second Reinhold Messner?

I’m neither happy nor sad about it. Everyone has the right to decide their own life. After completing his studies in molecular biology, Simon has decided for the time being to take a kind of interim period in the mountains, because he is an enthusiastic climber and mountaineer. I don’t tell him what to do with his life.

- Awards

- Mountain sports

- Bike

- Fitness

- Health

- ISPO Munich

- Running

- Brands

- Sustainability

- Olympia

- OutDoor

- Promotion

- Sports Business

- Textrends

- Triathlon

- Water sports

- Winter sports

- eSports

- SportsTech

- OutDoor by ISPO

- Heroes

- Transformation

- Sport Fashion

- Urban Culture

- Challenges of a CEO

- Trade fairs

- Sports

- Find the Balance

- Product reviews

- Newsletter Exclusive Area

- Magazine

![mb-170504-kaltenbrunner By ascending the K2 in 2011, Gerlinde Kaltenbrunner was the first woman ever to ascend all eight-thousanders and the first who managed this without additional oxygen. However, the 1970 born Austrian is not keen on records. " If it was all about records, I would have taken the easiest route everywhere [...] Being the first is not important to me".](/sites/default/files/styles/gallery_teaser/public/b/79/70/79706302-imageData.jpg?h=8fe3b20d&itok=7wqkZrnn)